Frank Keim produces artwork and information on the many different birds that can be encountered at the Peat Ponds. Here you can see the past work and content provided by Keim and identify the many various birds you may meet on your next trip to the ponds.

Yellow-rumped Warbler

Birders don’t call this little guy “butter butt” for nothing. The bright patches of butter yellow under its wings, on its topknot, and on its rump earn it both its common name and its nickname. Its scientific name, Dendroica coronata, means, “crowned tree dweller.” It is also called Myrtle warbler and is Alaska’s most numerous warbler, nesting only in mixed deciduous and spruce woods.

In addition to insects, this little guy also eats northern berries, including cranberries, bunchberries and blueberries, an ability unique among Northern warblers. Where most others are strictly insect eaters, Myrtles are more flexible in their diet since they can digest the wax coatings on berries. This allows them to stay later in the fall and arrive earlier in spring than their Alaskan cousins.

When the Myrtles arrive here, they come in waves. The males come in the vanguard, drifting through the treetops of spruce and still leafless aspens, birch and poplar. If you listen closely, you might hear the males singing their weak junco-like trill as they move through the area.

After a male sets up his home territory and the females begin to arrive, he changes his tune and sings a high-pitched, sidl sidl sidl sidl sidl seedl seedl seedl seedl, trying to attract an eligible female to be his mate. When a female enters his claimed nesting ground, he follows her everywhere, fluffing up his side feathers, raising his wings and colorful crown feathers, fluttering and calling sweetly.

This usually does the trick, and soon afterward the female builds a nest high on a horizontal limb of a spruce or deciduous tree. She shapes it in the form of an open cup using bark, twigs and wildflowers, then lines it with hair and feathers so they curve over and partially cover the top of the nest. As Myrtles are early nesters here, they must protect their eggs from the cold.

Four or five creamy white, brown-splotched eggs are laid, then incubated mostly by the mother bird (though the male may sometimes help out). In 12-13 days the young hatch, and both parents begin to feed them in earnest. They are nestlings for only another 10-12 days, when they leave the nest. Two or three days later they are able to fly short distances and follow their father around to be fed while mom begins brooding a second clutch of eggs.

In winter I have seen these migrant warblers in Mexico and Central America where they are known as “chipes” (after their winter call) and “reinitas” (“little queens”). Since they can live for about six years, the male birds you see in your backyard may be the same ones every year.

Horned Grebe

With its red eyes and tufted yellow ear feathers that often look like horns during mating season, the Horned grebe is from a family of birds that is one of the mostly perfectly adapted to water in the world. With their partially webbed, lobed toes, Horned grebes can dive and swim as rapidly and efficiently underwater as loons in search of food items, such as aquatic insects and their larvae, crustaceans, leeches, tadpoles and small fish. When alarmed, they can dive so swiftly they have been given the names “hell-diver” and “water witch”. And if a predator hawk or falcon swoops in while the adult grebes are piggybacking their downy chicks, they will dive underwater with the young holding tightly on their backs.

Courtship displays of these grebes are sometimes beyond belief. After rising to a vertical position in the water of an open pond or marsh with their head feathers fully erect, both male and female turn their heads rapidly back and forth in the same direction. They then dive and surface with bits of bottom weed in their bills, racing across the surface of the water side by side carrying their weeds. When the female decides her mate is worthy, they both begin to build their nest in shallow wate among reedy marsh growth. The nest turns out as a floating heap of wet plant material with a depression in the middle of it for the eggs. The pair finally attaches it firmly to standing vegetation. Mating and egg-laying begin immediately.

Usually 4-6 whitish to pale green or buff eggs are laid, but these soon become stained by the tannin from the pond on the feathers of both adults who incubate equally for 22-25 days. The young can swim and dive soon after hatching, fed and attended by both parents, often hitching rides on their backs. It takes almost two months for the young to make their first flight, a long time compared to other waterfowl.

Even for their parents, though, flight is a challenge, and after they establish their nesting territory, they rarely fly. This is because their legs are located so far back on their body, and it takes a lot of effort for them to patter across the surface of the water and become airborne. Like loons, who have the same body design, they may sometimes become trapped and starve to death if waters freeze quickly overnight and remain frozen.

An interesting tidbit about their eating habits is that adult birds regularly eat some of their own feathers, enough of them that their stomachs contain a matted plug of them. This plug may function as a filter and hold fish bones in the stomach until they are digested. The parents feed feathers to their chicks to get the plug started early.

Something else unique about these grebes is the way they sleep or rest. They put their neck on their back with their head off to one side, facing forward. They keep one foot tucked up under a wing and use the other one to maneuver in the water, so that they float with one “high” side and one “low” side.

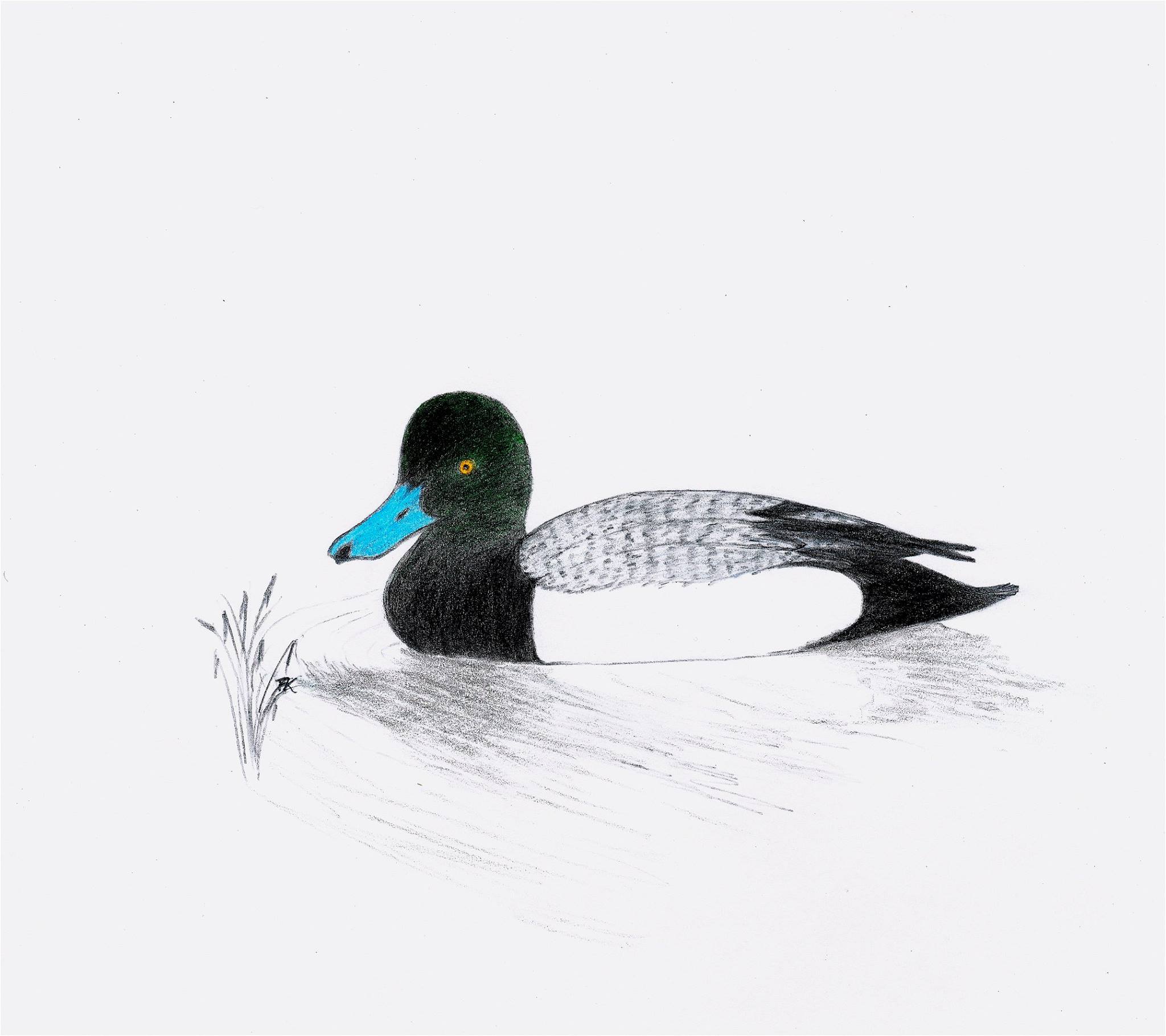

Greater Scaup

The Greater scaup, like its slightly smaller cousin, the Lesser scaup, is a diving duck. Most of the year it feeds underwater, using its feet to dive in saltwater bays and estuaries for shellfish. During summer, however, it acts more like a dabbling duck (mallard, wigeon) because it nests near the shallow water shores of lakes, ponds and marshes. Then its diet changes to freshwater snails, aquatic insects and crustaceans, tadpoles, small fishes and plant foods, such as pondweeds.

Scaups begin courting mostly in late winter and early spring while still wintering down south and during migration north to their nesting grounds. Often several males court one female, sharply throwing their heads back, bowing with the tip of their bill lowered to the water, then with bill raised high, they flick their wings and tail while uttering a soft, fast whistling, weew-weew-whew. The female responds with a low, arrrrr.

The female chooses the nest site and builds the nest in a shallow depression, lining it with dead plant material and her own down. Several females may nest close together in a loose colony.

As soon as his mate has laid the last of her 5-11 olive-buff colored eggs and begins to brood them the male duck takes off never to return for large freshwater lakes or saltwater estuaries. After the mother duck incubates the eggs for almost a month, they all hatch at about the same time and the ducklings follow her to water shortly afterward. Two or more families may join together,

tended by one or more females. The young feed themselves and take their first flight a month and a half after hatching.

The Greater scaup has many common names, including greater bluebill because of its blue bill. The name “scaup” probably comes from the English term that alludes to ducks that feed on scaups or scalps – beds of shellfishes. Its scientific name, Aythya marila, means “seabird of charcoal embers,” referring to its black head (with a green iridescence in the sun), neck, breast and tail. As a diving duck, it has small, pointed wings that make it easier for underwater swimming. But its heavy wing-loading (ratio of small wings to big body) requires it to run across the top of the water to build momentum before

taking off.

Peregrine Falcon

Adult males and females both share similar appearances, with a mostly dark gray back and head and a black-speckled white belly. They both have the telltale sideburns, or “whiskers,” as some refer to them. However, the female is larger than the male, as she is the one who produces the eggs and does the brooding. Before that happens, there is an extended month-long courtship period with cooperative hunting trips and absolutely spectacular ritual courtship flights. In these flights the male dives and pirouettes and somersaults around the female.

After making her choice, the pair quickly sets up their household. Called an aerie, this home will be high on a convenient cliff or bluff overhanging a food source: a swallow colony or a river with plenty of ducks. As with all falcons, a true nest is never built – only a scrape on an inward sloping ledge or a small cave. They may use this same aerie, or one nearby, every year for their entire lives. Usually 3-4 reddish-brown spotted cream-colored eggs are laid, which hatch a month later into little white fuzz balls. About five weeks after hatching, the now sleek young falcons make their maiden flights, earnestly prompted by their parents. Then they must learn how to hunt for themselves, which their parents teach them by showing them how to first dive on each other, then on different species like the Raven.

The peregrine was, until fairly recently, one of the most widespread of all bird species. Their presence reached to the ends of the Earth other than Antarctica. Since the widespread use of the insecticide DDT in the 1950’s, however, the species became almost extinct in many parts of the world, including the United States. Only since the Endangered Species Act of 1973 has it made a comeback, mostly through efforts by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

All content and artwork by Frank Keim.